2.1.3. Governing AI Without Halting Innovation

Governing AI Without Halting Innovation¶

"Effective AI governance is not about choosing between control and innovation—it's about designing oversight that enables both."

Artificial intelligence promises extraordinary benefits, life-saving diagnoses, personalized education, climate modeling, and more. But alongside these promises come real harms: discriminatory algorithms, opaque decisions, misinformation engines, and surveillance tools. Policymakers now face a defining question:

Can we regulate AI systems without slowing the innovation that drives them?

This is known as the governance-innovation paradox. Overregulation risks suffocating experimentation, especially for startups and researchers. Underregulation risks societal harm and loss of public trust. The challenge is not to pick one or the other, but to build governance that guides innovation safely and fairly. For AI to be truly trustworthy, governance must not merely control AI, it must inspire confidence, promote fairness, and earn the public’s trust through enforceable accountability. One example of this balance in practice is Singapore’s AI Verify that operationalizes accountability while preserving space for innovation.

AI Verify – Singapore’s Approach to Lifecycle Accountability:

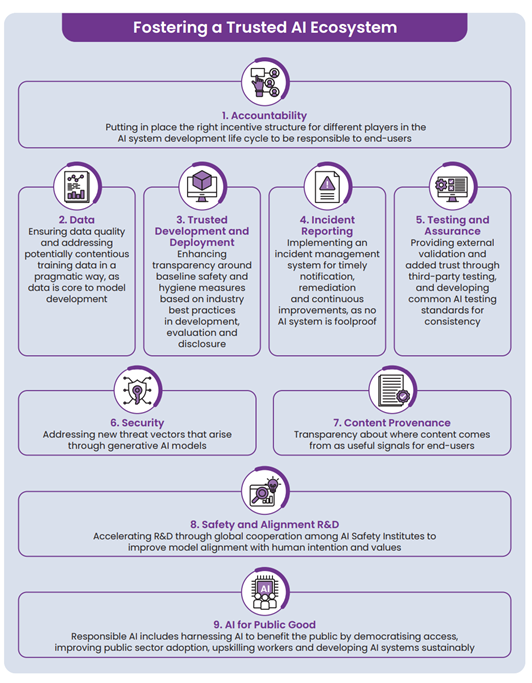

While many countries continue to wrestle with the governance-innovation paradox, Singapore offers a practical response through a tool called AI Verify. Developed by the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), AI Verify is a voluntary self-assessment framework and software toolkit that allows organizations to evaluate the trustworthiness of their AI systems before deployment. It transforms ethical principles like fairness, transparency, and explainability into concrete, testable practices without placing a regulatory burden on early innovation through the ecosystem as explained in the figure 15.

AI Verify operates on two levels: technical tests and process checks.

-

The technical layer evaluates supervised machine learning models (both classification and regression) using tabular or image data to assess how the model performs in terms of bias, robustness, and explainability.

-

The process checks, meanwhile, assess the organization's governance structures for example, how oversight is conducted, whether explainability documentation exists, and how risks are monitored across the AI lifecycle.

Rather than functioning as a compliance regime, AI Verify acts as an internal readiness tool, helping companies especially in high-impact sectors demonstrate responsible development aligned with global principles such as those outlined in ISO/IEC 42001. However, it is not without limits: the core framework currently focuses on supervised learning models and does not yet offer full integration for generative AI or large language models (LLMs).That said, the AI Verify Foundation has recently launched Moonshot, a separate modular tool for evaluating and red-teaming LLM applications, a signal that LLM-specific governance tools may be integrated into the broader framework in the future.

By embedding trust requirements directly into development workflows, AI Verify illustrates how governance and innovation need not be opposing forces but can be co-designed to support both confidence and competitiveness in AI ecosystems. This dual-layered structure is further reinforced by Singapore’s broader vision for fostering a trusted AI ecosystem, which highlights nine interrelated components including accountability, incident reporting, testing, content provenance, and alignment with public good objectives.

The Risk of Doing Nothing

Some argue that regulation kills innovation. But failing to govern AI carries consequences that may be far more damaging, both to the public and to the long-term future of the technology itself.

Examples of Harm from Lack of Governance:

-

Predictive policing tools over-targeting minority communities due to flawed crime data 1.

-

Deepfake generators spreading misinformation, eroding public trust in media 2.

-

Generative AI chatbots (like Lee Luda) producing offensive or unlawful speech due to poorly filtered training data.

In each case, the absence of trustworthy governance didn’t create innovation, it created risk. And in many cases, the resulting backlash led to shutdowns, lawsuits, and the erosion of trust ironically setting innovation back further.

Even when AI causes harm, no one may be legally responsible. In many jurisdictions, AI systems are not recognized as legal entities and deploying organizations often frame them as “decision support tools.” If no one is explicitly assigned oversight, there may be:

-

No one to investigate

-

No legal liability

-

No internal or external consequences

and education records to flag people as "high-risk" fraud suspects.

Case Study 009: The SyRI Algorithm and Welfare Surveillance (Location: Netherlands | Theme: Transparency and Data Governance)

📌 Overview

SyRI (System Risk Indication) was an algorithmic system used by the Dutch government to detect potential welfare fraud. It aggregated data from housing, tax, education, and employment records to create risk profiles. Individuals were flagged as “high risk” for fraud investigations without being notified or given access to the decision-making criteria.

🚧 Challenges

There was no audit mechanism, transparency standard, or user recourse. Critics argued the system disproportionately flagged low-income and immigrant communities.

🎯 Impact

Affected individuals were marked as high-risk without explanation. The system drew criticism for violating privacy and data protection principles.

🛠️ Action

Legal challenges were brought by civil society organizations. The courts assessed the system’s compliance with constitutional and human rights protections.

🎯 Results

In 2020, SyRI was ruled unconstitutional by a Dutch court. The case drew international attention to the risks of opaque government AI systems.

As detailed in Case Study 009, the Dutch government used SyRI to profile citizens as potential welfare fraud suspects. The system processed sensitive data from multiple sources housing, tax, employment, and education and flagged individuals as “high risk” without informing them or offering a way to contest the decision.

Those flagged faced reputational harm, financial hardship, and social exclusion often based on flawed or biased data. Independent evaluations revealed the system disproportionately targeted immigrants and low-income residents yet no public official, agency, or contractor was held accountable.

Figure 16 makes the consequences of invisible algorithmic power visible. On the left, a low-income neighborhood is subject to digital scrutiny: residents are marked, monitored, and silently categorized by facial recognition overlays and embedded surveillance infrastructure. Their identities are flagged, not because of any individual wrongdoing, but because of their postcode.

On the right, a wealthier neighborhood exists without intrusion—free from algorithmic suspicion, untouched by the same datafication mechanisms. This contrast exposes a harsh truth: SyRI did not profile based on behavior—it profiled based on poverty.

As UN Special Rapporteur Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, expressed his concerns about SyRI in a letter to the Dutch court on 26 September 2019 3: “Whole neighborhoods are deemed suspect and are made subject to special scrutiny, which is the digital equivalent of fraud inspectors knocking on every door in a certain area and looking at every person’s records in an attempt to identify cases of fraud, while no such scrutiny is applied to those living in better off areas.”

Although SyRI was eventually ruled unconstitutional by a Dutch court, the legal process revealed that:

-

No single agency had oversight responsibility

-

No transparency mechanism existed for those impacted

-

No internal review board had flagged the system as discriminatory

A system may cause measurable harm, violate fundamental rights, and still escape meaningful accountability if no skateholder is clearly designated as responsible.

This case illustrates a dangerous accountability vacuum especially at the institutional governance level. This failure underscores the need for governance structures that are not only present, but functional where roles are clearly defined, and oversight is embedded. Fortunately, several modern approaches offer blueprints for doing just that, without stifling innovation.

Effective AI regulation doesn’t have to be restrictive. It can be:

-

Risk-based (e.g., the EU AI Act targets only high-risk applications),

-

Principles-based (e.g., Singapore’s AI Verify framework focuses on transparency and fairness),

-

Outcome-focused (e.g., ISO 42001 emphasizes continual improvement and organizational accountability).

Each of these governance approaches contributes to trustworthy AI ensuring that innovation is not only safe, but also aligned with societal values and ethical obligations.

The EU AI Act and the Risk-Based Approach

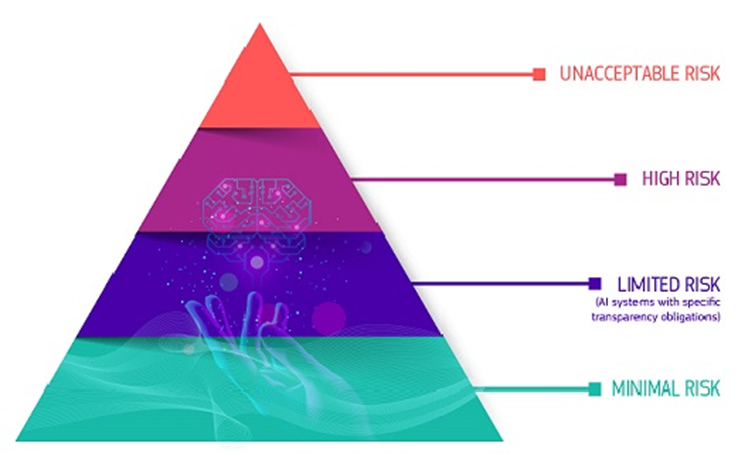

In 2021, the European Commission proposed the world’s first comprehensive AI regulation: the EU Artificial Intelligence Act. Instead of banning AI outright or regulating all AI the same way, the Act introduced a tiered risk framework as shown in Figure 17:

Unacceptable Risk:

AI systems considered a clear threat to fundamental rights, safety, or democratic values. These include:

-

Social scoring by governments

-

Subliminal manipulation that causes harm

-

Exploiting vulnerabilities of specific groups (e.g., children or persons with disabilities)

Status: Prohibited under the EU AI Act

High Risk:

AI systems used in applications where risks to health, safety, or fundamental rights are significant. These include:

-

Biometric identification and categorization (e.g., facial recognition in public spaces)

-

AI used in education or vocational training (e.g., scoring exams)

-

Employment and worker management tools (e.g., CV screening, promotion decisions)

-

Critical infrastructure management (e.g., water, gas, energy supply)

-

Access to essential services (e.g., credit scoring for loans, public benefits eligibility)

-

Law enforcement, border control, and judiciary applications

Status: Subject to strict obligations including (1) conformity assessments, risk management, transparency, human oversight, and data quality standards

- A formal process used to verify that an AI system meets specific legal or technical requirements, often required for high-risk AI under the EU AI Act.

Limited Risk:

AI systems that pose a moderate risk but still require transparency obligations. These include:

-

AI systems that interact with humans (e.g., chatbots)

-

AI used to generate or manipulate content (e.g., deepfakes, synthetic media)

Status: Must inform users that they are interacting with AI or viewing AI-generated content

Minimal Risk:

AI systems that pose little to no risk to users’ rights or safety. These include:

-

Spam filters

-

AI-enabled video game NPCs

-

AI recommendation engines for music or streaming services

Status: No specific obligations under the EU AI Act; general product safety laws apply

(Source)

This approach provides a middle path: protecting people from serious harm while leaving room for innovation in low-risk contexts. While the law is still under refinement, it has already influenced global policy discussions, including in Korea, Canada, and Brazil. Complementary tools like Singapore’s AI Verify and ISO/IEC 42001 strengthen this trend. AI Verify enables self-assessment for fairness and transparency, while ISO/IEC 42001 supports risk-based AI management at the organizational level.

Complementary tools such as Singapore’s AI Verify and international standards like ISO/IEC 42001 further support this trend. AI Verify enables self-assessment for fairness and transparency before deployment, while ISO/IEC 42001 and related frameworks offer risk-based management models to help organizations embed accountability across the AI lifecycle. For a detailed breakdown of how these ISO standards operate across system, organizational, and leadership levels.(Section 2.1.1)

When implemented effectively, such frameworks help organizations align AI development with legal requirements (e.g., GDPR, EU AI Act), foster transparency, and integrate ethical principles into strategic decision-making. They also support role assignment, internal audits, and impact assessments to ensure fairness and safety.

These models demonstrate that regulation and innovation are not opposites. In fact, clear governance frameworks can build trust, reduce uncertainty, and drive responsible progress.