2.2.1. From Principles to Policy- The Evolution of AI Governance

From Principles to Policy: The Evolution of AI Governance¶

Why are we still seeing AI systems cause harm, despite a decade of ethical promises?

The global AI community has spent years crafting vision statements and voluntary pledges committing to fairness, transparency, and human-centered design. These documents have raised awareness and shaped norms. But they’ve also failed often publicly.

Governments released national AI strategies. International bodies like UNESCO, OECD, and GPAI published ethical principles. Corporations released codes of conduct and responsible AI frameworks.

And yet, biased hiring systems, surveillance abuses, and exclusionary algorithms continue to cause real harm.

Why? Because these early responses were mostly: Voluntary, Fragmented and Unenforceable

They lacked accountability structures, oversight mechanisms, and operational tools to translate ethical intent into action. As detailed in Chapter 1, Case Study 007 analyzes Amazon’s internal résumé-screening tool, which penalized applications containing the word "women’s." Trained on a decade of hiring data, the model “learned” to downgrade applications that included terms like “women’s chess club captain”.

This bias wasn’t explicitly coded it emerged from historical patterns of underrepresentation in Amazon’s own hiring data. While the system was designed to improve recruitment efficiency, its deployment revealed a critical breakdown in AI governance which are tabulated in table 5.

Table 5: Governance Gaps in AI Hiring System Deployment

| Governance Element | ✅/❌ | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Intent to automate hiring and improve efficiency | ✅ | The system was designed to streamline recruitment and reduce manual screening. |

| Use of real-world historical hiring data | ✅ | The model was trained on 10 years of internal hiring records. |

| Fairness audit conducted before deployment | ❌ | No bias or demographic analysis was done before release. |

| Explainability mechanisms implemented | ❌ | No interpretability tools were used to interpret or validate rejection patterns. |

| Formal accountability assigned (e.g., ethics/compliance) | ❌ | No role or team was responsible for bias detection or ethical review. |

| Internal review triggered corrective action | ✅ | Internal concern led to the system being withdrawn. |

| Oversight or compliance checkpoint built into development | ❌ | No board, compliance role, or lifecycle audit mechanism was in place. |

| External communication or accountability to the public | ❌ | The model’s failure and withdrawal were not accompanied by public transparency or redress. |

Although the system was eventually withdrawn, it had already amplified bias and caused reputational harm. The case illustrates how partial governance without fairness checks, explainability, or role-based accountability fails to prevent systemic discrimination.

Trustworthy AI requires more than ethical intention it needs enforceable mechanisms, assigned oversight, and traceability at every stage of development.

Although the system was eventually withdrawn, it had already amplified bias and caused reputational harm. The case illustrates how partial governance lacking fairness audits, explainability tools, and role-based accountability fails to prevent systemic discrimination. These gaps reveal a broader issue: while ethical guidelines may exist, organizations often lack the practical infrastructure to operationalize them.

This is where lifecycle-based governance frameworks like AIGA begin to offer real possibility. By embedding accountability across strategic, organizational, and technical layers, such frameworks provide a structured way to align design decisions with compliance responsibilities. In the following section, we explore how AIGA transforms high-level principles into enforceable governance mechanisms across the entire AI system lifecycle.

TRAI Deep Dive: AIGA – A Finnish Framework for Lifecycle AI Governance

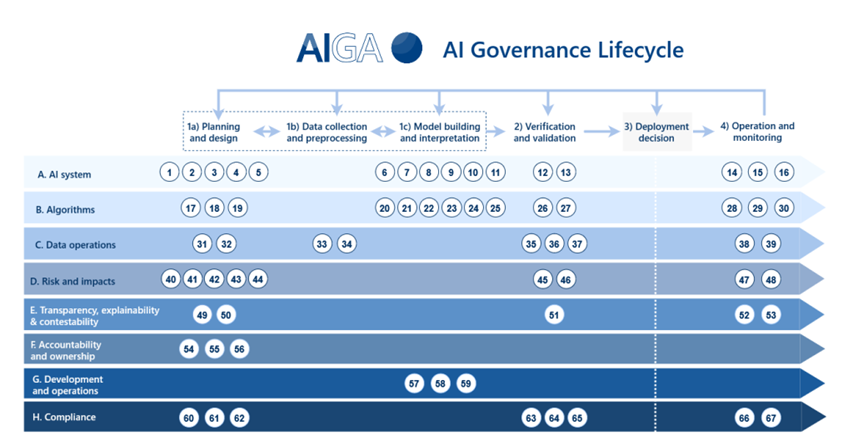

The Artificial Intelligence Governance and Auditing Framework (AIGA) was developed in Finland, through collaboration between the University of Turku and industry partners. It is a practical, lifecycle-based model (Figure 18) that supports responsible AI deployment across sectors and regulatory environments.

(Source)

AIGA exemplifies how operational governance can be implemented at scale, aligned with global standards such as the EU AI Act and ISO/IEC 42001.

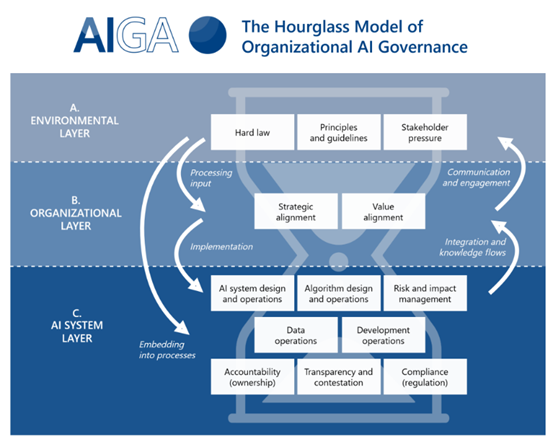

AIGA structures governance across three interconnected layers:

-

Environmental Layer – Legal frameworks, public trust, national strategies

-

Organizational Layer – Internal policy, ethics oversight, compliance infrastructure

-

AI System Layer – Technical transparency, explainability, post-market monitoring

(Source)

These are embedded within an Hourglass Model (figure 19) that connects top-level governance goals to system-level interventions. The framework also includes 67 governance tasks mapped to the OECD AI lifecycle, covering stages from design through post-deployment. Its primary strength lies in enabling organizations to demonstrate compliance and accountability without prescribing any one philosophical orientation. The model supports (1)audit-readiness, international interoperability, and responsible AI deployment across borders. As governments and institutions increasingly seek operational governance tools, AIGA offers a clear example of how accountability can be embedded directly into design and oversight systems.

- The condition of an organization or system being able to demonstrate compliance with laws, standards, or ethical commitments through documentation, monitoring tools, and governance processes.

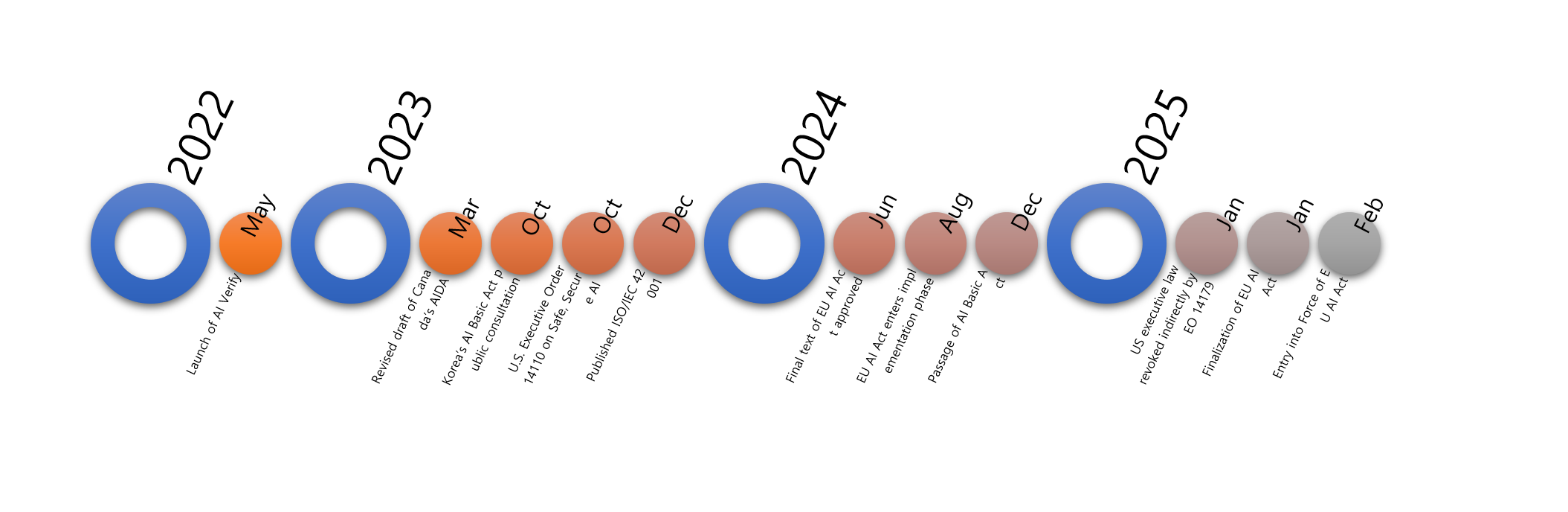

The shift toward enforceable governance is not theoretical it is happening in real time. The following milestones from 2023–2024 illustrate how countries and institutions are moving beyond voluntary principles toward binding legal and policy frameworks. The recent global AI Governance milestone as included in the Figure 20. This timeline highlights key national and international developments in AI governance between 2023 and 2024, illustrating the shift from voluntary ethical guidelines to enforceable legal and policy frameworks

Voluntary ethical frameworks were a necessary start, but they are not enough. Without legal enforcement and reliability measures embedded into organizational and system design, AI governance risks being reactive and ineffective. The transition to enforceable, lifecycle-wide policies is not optional, it’s already underway. Without legal backing, ethics alone cannot address the scale and urgency of AI’s societal impact. These failures raise a deeper question:

Who truly shapes AI governance, the public, or powerful private interests?