4.3. What Makes a Dataset “Trustworthy”?

What Makes a Dataset “Trustworthy”?¶

“Trust isn’t a label you apply to a dataset. It’s a property you design into it, deliberately, measurably, and continuously.”

We often hear the phrase, “a model is only as good as its data.” In low-risk applications, that may be a technical concern. But in high-stakes domains, healthcare, hiring, education, law enforcement, it becomes a moral obligation. A biased or misrepresentative dataset doesn’t just produce poor predictions. It can exclude communities, deny access, and amplify discrimination at scale.

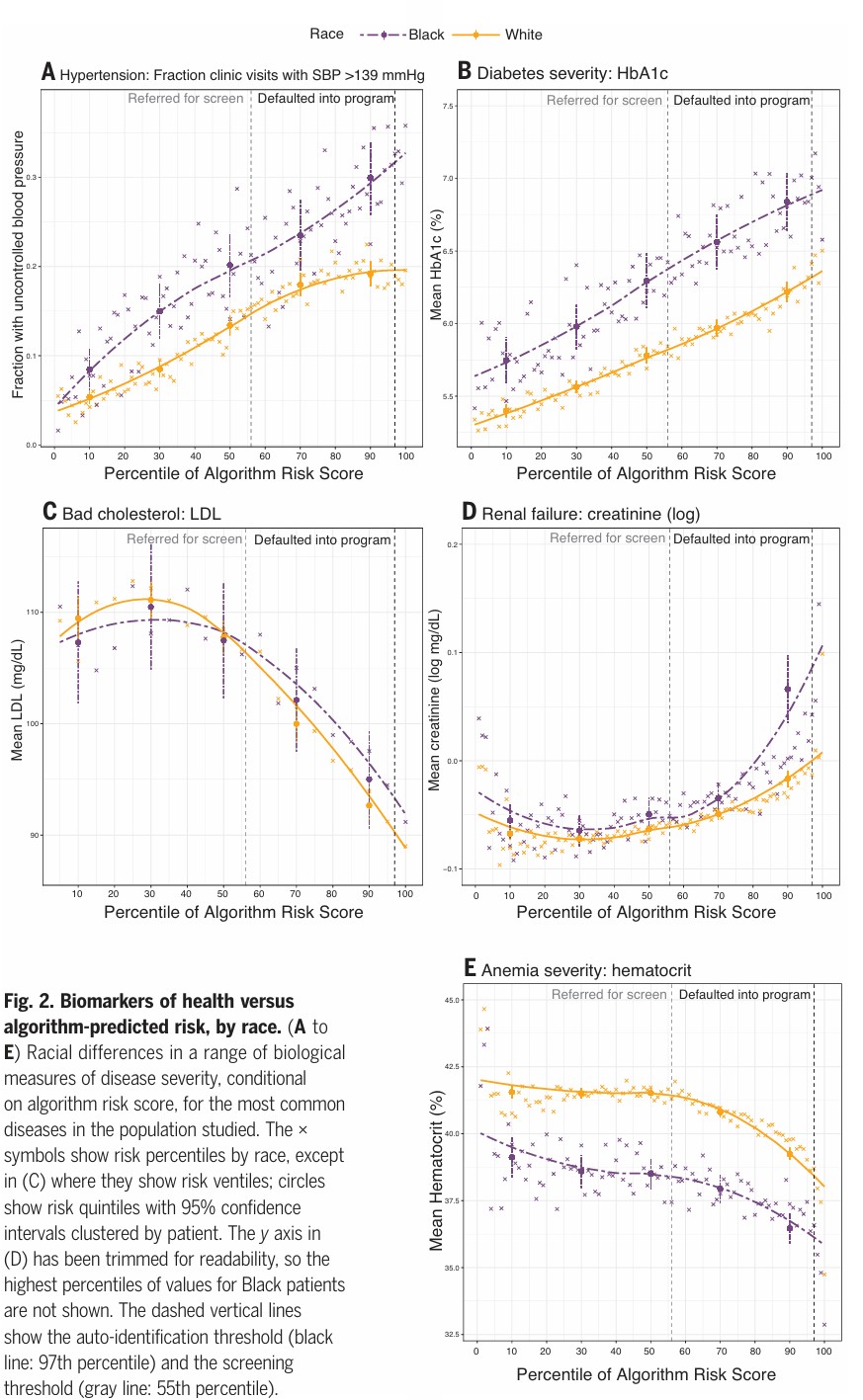

This figure compares clinical biomarkers to algorithm-predicted risk percentiles for Black and White patients across five conditions. Despite worse health indicators, Black patients often receive lower risk scores, revealing systematic underestimation and potential racial bias in healthcare algorithms.

Source

A Case in Focus: When Bias in Data Denies Medical Care¶

In 2019, a peer-reviewed study published in Science uncovered that a healthcare risk-prediction algorithm, used by major insurers and hospitals across the U.S., was systematically deprioritizing Black patients for follow-up care1. The model, trained on historical healthcare cost data, assumed that patients with higher prior costs required more care in the future.

But that assumption encoded structural inequality. Because of long-standing disparities in healthcare access and treatment, Black patients often incurred lower medical costs, not due to better health, but because of systemic underdiagnosis and undertreatment. As a result, the model assigned them lower risk scores, even when their medical needs were equal to or greater than their white counterparts.

This led to real-world harm:

- Lower risk scores meant fewer referrals and reduced care coordination

- Patients in need were excluded, not by medical reasoning, but by the dataset’s blind assumptions

- No audit process or metadata flagged the disparity before deployment

❗ The model didn’t fail technically. It failed because its dataset could not be trusted to represent everyone fairly.

Claiming Fairness Isn’t the Same as Proving It¶

Many organizations assert that their datasets are “balanced” or “representative.” But without concrete evidence, lineage logs, representation scores, stakeholder review, such claims are unverifiable.

For instance, ISO/IEC 5259-3:2024, Clause 6.3 defines data quality requirements including representativeness, completeness, and fitness-for-purpose2.

A trustworthy dataset must demonstrate:

- Documented provenance: Where the data came from, how it was labeled, and why it was selected

- Inclusive sampling and representation analysis

- Ethical review, especially for sensitive features like race, gender, or disability

- Bias audits and mitigation workflows using tools like FairMT-Bench, DiagSet, or ReIn

- Ongoing monitoring, not just a one-time evaluation

📊 Tools like ReIn and FairMT-Bench provide structured fairness evaluations across intersectional demographics and model test cases3.

When Datasets Fail, the Consequences Are Structural¶

Imagine a public housing algorithm trained on 10 years of applicant data. If that data underrepresents immigrant families or disabled applicants, whether by design, omission, or historical bias, the model will replicate those exclusions.

The result? : Some families may be denied benefits not because they’re ineligible, but because the system was never trained to see them.

A trustworthy dataset isn’t something you stumble upon. It must be deliberately constructed.

📘 ISO/IEC 38505-1:2017 recommends embedding governance roles and stakeholder checkpoints at each phase of data use4.

Trustworthiness begins with fairness-by-design:

- Ensuring inclusion and representation from the earliest stages of sampling and labeling

- Auditing for gaps and redundancies, who is missing? Who dominates?

- Linking datasets to rights-aware metadata (licensing, consent, origin)

- Testing datasets in context, across tasks and demographic slices

- Enabling continuous validation, especially for bias drift or group-level harms

Bibliography¶

-

Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019). Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 366(6464), 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342 ↩

-

ISO/IEC 5259-3:2024(E). Artificial Intelligence , Data quality for analytics and machine learning , Part 3: Data quality management process. ↩

-

Mitchell, M., et al. (2019). Model Cards for Model Reporting. FAT* Conference. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287560.3287596 ↩

-

ISO/IEC 38505-1:2017. Governance of data , Application of ISO/IEC 38500 to the governance of data. ↩