7.3.3. Who Gets to Change the Model?

Who Gets to Change the Model?¶

When deployed AI systems face feedback, drift, or public scrutiny, change often feels like the obvious solution, tune the parameters, retrain the model, adjust the thresholds. But each revision, no matter how minor, carries the risk of unintended consequences. A new model may improve accuracy but introduce unfairness. A retraining cycle might patch a bug but erode interpretability.

Yet in most organizations, these changes are implemented without any formal decision path or oversight authority. Updates are filed as technical maintenance rather than governance events, and this is where trust begins to unravel.

A telling example is Facebook’s 2018 News Feed algorithm update. In an effort to promote “meaningful social interactions,” the platform adjusted ranking weights to favor engagement. Internally, engineers flagged that this boosted divisive content. But no formal revision review process was in place to stop the rollout. The system didn’t fail technically, it failed governance-wise1.

When change is treated as a product tweak rather than a trust decision, ethical risks become invisible.

That’s why standards bodies and AI governance frameworks now insist that post-deployment change must be governed, not improvised.

The ISO/IEC 23894:2023 AI risk management standard recommends that organizations treat model updates as high-risk change events requiring documentation, reassessment of hazards, and formal approval pathways2. Similarly, the EU AI Act (Annex VII) classifies major system modifications as compliance triggers, meaning an update can reset your legal obligations3.

These perspectives reflect a growing consensus: oversight doesn’t end at deployment. It continues as long as the system evolves.

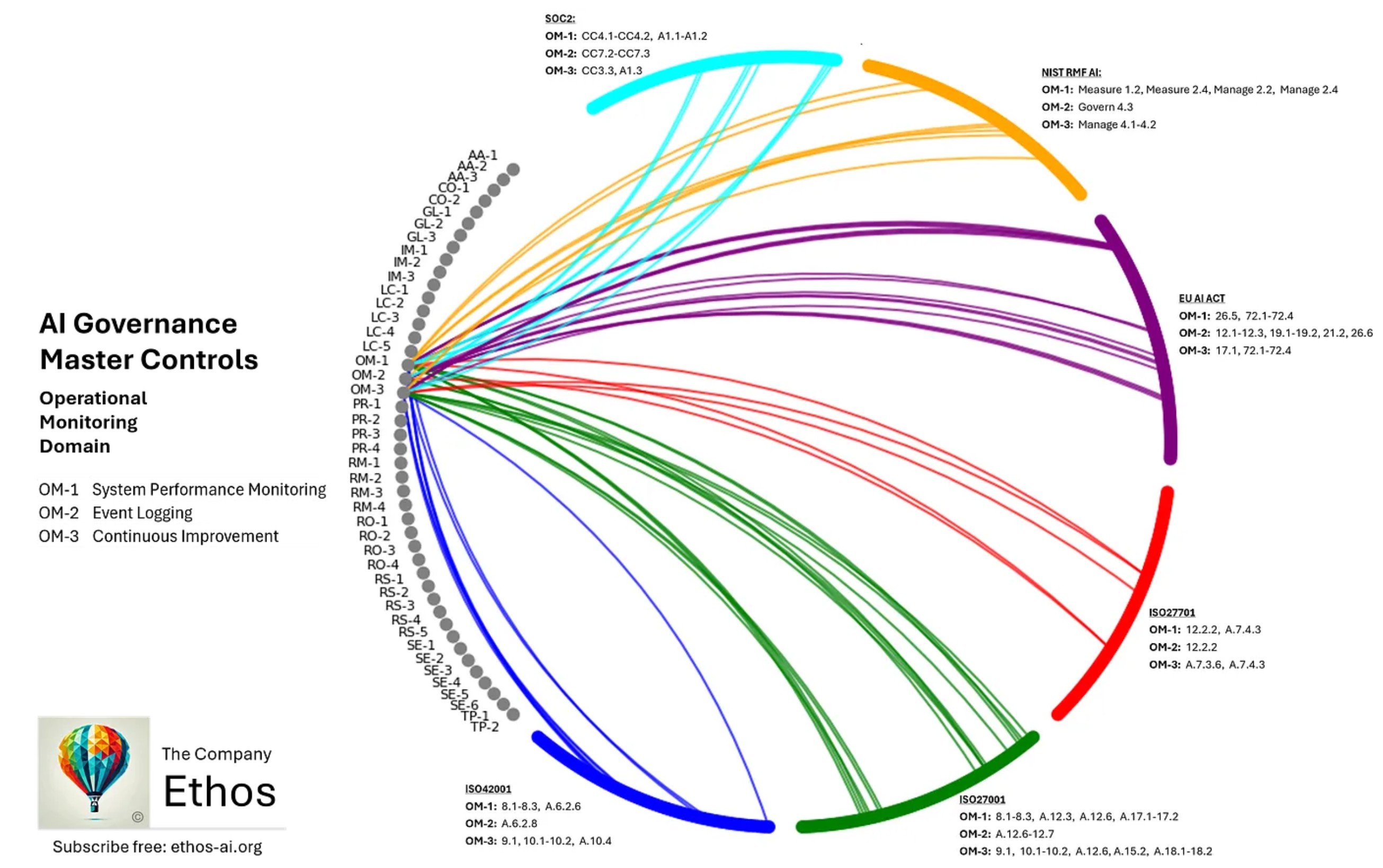

This is further reinforced in industry-aligned governance mappings like James Kavanagh’s AI Governance Mega-map, which identifies IM-3: Incident Analysis and Improvement and OM-3: Continuous Improvement as central to trustworthy AI operations4. Together, they provide a structured loop for post-deployment learning:

- IM-3 ensures that incidents, whether model drift or ethical complaints, are reviewed systematically, root causes identified, and changes implemented with traceability.

- OM-3 extends this by linking performance monitoring and user feedback to documented improvement plans with timelines, review cycles, and risk-adjusted priorities.

These controls make one principle clear: improvement is not a fix, it is a governed action.

Table 58: Models of Post-Deployment Change Governance

| Governance Model | Description | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|

| Ad Hoc | Developers or teams make unreviewed changes | High risk |

| Policy-Aligned | Changes follow internal rules but lack third-party oversight | Medium trust, internal only |

| Audited Change Board | Proposed updates are reviewed by cross-functional teams | Improved traceability |

| Regulatory Notified | Changes reported or cleared with external regulators | Strongest for high-risk systems |

As systems grow more powerful, change without authority becomes change without accountability.

The following figure illustrates how these controls fit within broader operational governance responsibilities, emphasizing the link between monitoring, escalation, and structured improvement:

This figure from Kavanagh (2025) maps ISO/IEC 42001, ISO/IEC 27001/27701, NIST RMF, SOC2, and the EU AI Act into three interconnected layers: monitoring, incident response, and continual improvement—closing the governance loop for post-deployment AI trust.

Ultimately, the authority to approve change must be explicitly assigned, not inferred. Change logs, audit trails, and update governance boards are not bureaucratic add-ons; they are mechanisms of institutional trust.

You’re not just updating a model, you’re updating what the public experiences. Someone must own that choice.

Thinkbox

“Every model update is a governance event.”

“Every model update is a governance event.”While code updates go through CI/CD pipelines, model updates often skip legal or compliance review.

The EU AI Act (Annex VII) states that major changes to a high-risk model require recertification. ISO/IEC 23894 treats model retraining as a new hazard assessment.

That means:

- A fine-tuned model may need a new risk documentation cycle

- Revisions must be tracked via audit-ready changelogs

- Stakeholders must be notified of impact (especially in healthcare, finance, or justice systems)

Change isn’t just technical, it’s regulatory.

True or False: Oversight Myths in AI Monitoring

Quickfire Test: Are these statements True or False?

Use what you’ve learned across 7.1–7.3 to decide.

-

If an alert system exists, the AI deployment is considered trustworthy.

-

Reviewer roles and fallback authority must be documented before deployment.

-

A dashboard that floods the reviewer with too many metrics improves safety.

-

Complaints are not part of governance unless linked to documented actions.

-

ISO/IEC 24028 considers responsiveness to user input a key factor in operational trustworthiness.

Bibliography¶

-

Horwitz, J., & Seetharaman, D. (2021). Facebook tried to make its platform a healthier place. It got angrier instead. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-algorithm-change-zuckerberg-11631654215 ↩

-

ISO/IEC. (2023). ISO/IEC 23894: Artificial Intelligence , Risk Management. International Organization for Standardization. https://www.iso.org/standard/81227.html ↩

-

European Union. (2024). EU Artificial Intelligence Act – Final Text (Annex VII). https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/the-act ↩

-

Kavanagh, J. (2025). AI Governance Mega-map: Operational Monitoring and Incident Management. Doing AI Governance. https://www.ethos-ai.org/p/ai-governance-mega-map-ops-and-incidents ↩